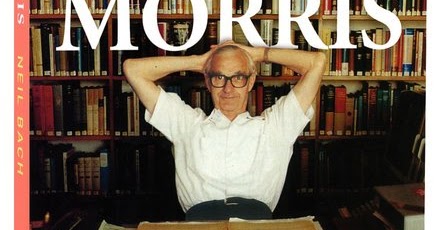

In his classic exposition The Apostolic Preaching of the Cross (1955; third edition 1965) Leon Morris dedicates a chapter to examining the phrase ‘the blood.’ In the chapter, Morris is responding to a particular view, viz. the idea that when Scripture speaks of an offering of blood, the term refers to the offering of life—life given and life released. He refutes this view showing that references to blood in relevant Old and New Testament texts speak not of life but death, and often a violent death. This contention holds true in contexts of sacrifice, and by extension, of Jesus’ death and Jesus’ blood: the ‘blood’ means his death.

In his classic exposition The Apostolic Preaching of the Cross (1955; third edition 1965) Leon Morris dedicates a chapter to examining the phrase ‘the blood.’ In the chapter, Morris is responding to a particular view, viz. the idea that when Scripture speaks of an offering of blood, the term refers to the offering of life—life given and life released. He refutes this view showing that references to blood in relevant Old and New Testament texts speak not of life but death, and often a violent death. This contention holds true in contexts of sacrifice, and by extension, of Jesus’ death and Jesus’ blood: the ‘blood’ means his death.

Morris begins by examining every reference to ‘blood’ in both testaments, and categorising them. The word dām is used 362 times in the Old Testament and these are grouped in the following categories: death with violence of some kind (203x), connecting life with blood (7x), eating meat with blood (17x), sacrificial blood (103x), and other uses (32x).

From these figures it is clear that the commonest use of dām is to denote death by violence, and, in particular, that this use is found about twice as often as that to denote the blood of sacrifice. … As far as it goes, the statistical evidence indicates that the association most likely to be conjured up when the Hebrews heard the word ‘blood’ was that of violent death (pp. 113-114).

Even in Leviticus 17:11 where the connection between blood and life is at its most explicit, the meaning of the verse is of life given up in death. “It is the ‘life of the flesh’ that is said to be in the blood, and it is precisely this life which ceases to exist when the blood is poured out” (117). “Blood shed stands, therefore, not for the release of life from the burden of the flesh, but for the bringing to an end of life in the flesh. It is a witness to physical death, not an evidence of spiritual survival” (118, citing A. M. Stibbs). Morris concludes his examination of the Old Testament witness to blood as follows:

We conclude, then, that the evidence afforded by the use of the term dām in the Old Testament indicates that it signifies life violently taken rather than the continued presence of life available for some new function, in short, death rather than life, and that this is supported by the references to atonement (121).

The Greek term αἷμα is found ninety-eight times in the New Testament, of which about thirty-five refer to the blood of Christ. Like the word ‘cross,’ blood is used as a metonymy for the death of Christ ‘in its salvation meaning’ (126). This meaning includes the ideas of Christ’s blood as a ransom-price, a means of purging, or the element to ratify a solemn covenant (127).

The blood of Jesus, therefore, refers to the death of Christ by which we are reconciled to God (Colossians 1:20), having been justified ‘by his blood’ and so saved from wrath through his death (Romans 5:9-10). We have been made close to God through his blood (Ephesians 2:13), for his blood has secured an eternal redemption for us (Hebrews 9:12; 1 Peter 1:18-19), and has purified our hearts, granting us confident entry into the very holiest of places, the divine presence itself (Hebrews 9:14; 10:19).

The blood of Jesus, therefore, refers to the death of Christ by which we are reconciled to God (Colossians 1:20), having been justified ‘by his blood’ and so saved from wrath through his death (Romans 5:9-10). We have been made close to God through his blood (Ephesians 2:13), for his blood has secured an eternal redemption for us (Hebrews 9:12; 1 Peter 1:18-19), and has purified our hearts, granting us confident entry into the very holiest of places, the divine presence itself (Hebrews 9:14; 10:19).

If it is the case as Hebrews 9:22 states, that without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sins, was Jesus’ death necessary? Did God require the death of the Son in order to extend forgiveness? Why can God not simply forgive without suffering, violence, atonement and death? Does God require payment before he will forgive? That Jesus died is evident, as is the violence of his death. But is God responsible for this violence? Did God require this violence before he could forgive sins? Is God’s forgiveness predicated on violence in such a way that it legitimises violence as a necessary or at least inevitable feature of inter-personal relations and reconciliation? Did God purpose the violence of the cross or more simply foreknow that violence? Is God implicated in Jesus’ death as a God who is thus inherently and so also, eternally violent?

Acts 2:23 addresses but does not resolve this matter: “This Jesus, delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, you crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men…” Peter repeats his charge against the Jewish leaders in Acts chapters 3, 4 and 5:

The God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, the God of our fathers, glorified his servant Jesus, whom you delivered over and denied in the presence of Pilate, when he had decided to release him. But you denied the Holy and Righteous One, and asked for a murderer to be granted to you, and you killed the Author of life … And now, brothers, I know that you acted in ignorance, as did also your rulers. But what God foretold by the mouth of all the prophets, that his Christ would suffer, he thus fulfilled (vv. 13-15, 17-18; cf. 4:10, 24-28; 5:28-30).

Peter lays the blame for Jesus’ violent death at the feet of the Jewish leaders, and also insists that this activity was in accordance with the divine purpose revealed in Psalm 2. Although this is a classic example of the tension between divine providence and human responsibility, it may be best to understand Jesus’ violent death as the activity of the human participants in the drama, and see in Peter’s citation of Psalm 2, divine awareness of a broader pattern of human action coming to expression in this case specifically. As such, God has not acted violently as much as given himself into the hands of a violent humanity which consistently rejects the call and claim of God.

One of the features of Barth’s mind and work concerns the relentless nature of his questions by which he penetrates his topic, lays open its inner dynamic, and presses his criticism. Barth probes and interrogates his conversation partners by means of his questions. An example is seen in Church Dogmatics II/2:63-64. Barth has shown that the Reformers and their heirs want to look to Jesus as the ground of their assurance with respect to divine election. Strong statements are found in the tradition, by Luther, Melanchthon, Calvin, Bullinger, the Helvetic Confession, the Formula of Concord, and so on. Nevertheless Barth subjects the tradition to a dozen probing questions, although ultimately, they are all variations of the one central question:

One of the features of Barth’s mind and work concerns the relentless nature of his questions by which he penetrates his topic, lays open its inner dynamic, and presses his criticism. Barth probes and interrogates his conversation partners by means of his questions. An example is seen in Church Dogmatics II/2:63-64. Barth has shown that the Reformers and their heirs want to look to Jesus as the ground of their assurance with respect to divine election. Strong statements are found in the tradition, by Luther, Melanchthon, Calvin, Bullinger, the Helvetic Confession, the Formula of Concord, and so on. Nevertheless Barth subjects the tradition to a dozen probing questions, although ultimately, they are all variations of the one central question: