In twelfth century Western Europe, independent schools were springing up alongside the older cathedral schools as a precursor to the development of the universities. There was a market for students as more and more people wanted the kind of education that prepared them for the growing civil service required by both church and state. According to Gillian Evans,

In twelfth century Western Europe, independent schools were springing up alongside the older cathedral schools as a precursor to the development of the universities. There was a market for students as more and more people wanted the kind of education that prepared them for the growing civil service required by both church and state. According to Gillian Evans,

A school did not need buildings or organization or a syllabus. Would-be masters could simply set themselves up and lecture to students, so they needed to be in places where potential fee-paying students might be found. There was rivalry. Masters tried to capture one another’s students, sometimes adding critical comments about one another’s opinions in their lectures….

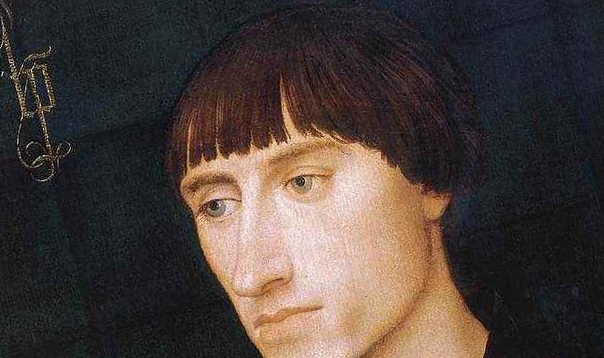

One of the most notorious of these wandering masters, Peter Abelard (1079-1142) describes in his History of My Calamities how he went to hear Anselm of Laon (d. 1117) lecture at the cathedral school at Laon, with the express purpose of capturing some of his students. Abelard had already made his name as a daring logician and now he wanted to move on to theology, an obvious career move because it was regarded as a more advanced and prestigious subject. … Abelard was not a trained theologian. He had, however, skills in linguistic analysis from his knowledge of logic, and he began to apply these to the interpretation of the text of Scripture with disturbing results. Students loved this for its danger and novelty. They flocked to hear him. He was able to set up a school in Paris at St Geneviève on the left bank of the Seine (Evans, The Roots of the Reformation, 161-162).

I had to smile at Abelard wanting to “move onto theology, an obvious career move…”, and also at the rivalry between teachers and schools. Some things change and some things don’t.

It is also evident that some things about students haven’t changed much either, though perhaps this can be forgiven. Part of the joy of education is the opportunity to explore novel and even dangerous ideas. Problems occur when such education is broken off too quickly, and the novel is embraced uncritically, or worse, because it is novel. Sometimes, though, the novel may prove to be a breakthrough, a new paradigm that advances knowledge and opens new vistas of understanding. This has happened time and again in the history of theology. It is evident, however, that Evans does not think much of Abelard’s innovations.

The book promises to be a rich and rewarding read not only for youth ministers, but for all who love and serve in the church. The

The book promises to be a rich and rewarding read not only for youth ministers, but for all who love and serve in the church. The