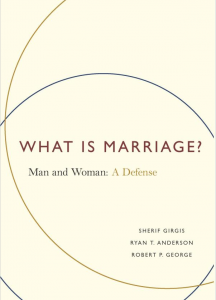

The first three parts of this series (see Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3) detailed the positive arguments made by the authors for a “conjugal” view of marriage. The remainder of the book—chapters four through six, the conclusion, and the appendix—address objections to the view that the authors have presented. The fourth chapter, “What’s the Harm?”, addresses an objection commonly put by advocates of same-sex marriage, that extending the institution to same-sex couples will increase the blessings of marriage while doing no harm to existing marriages or marriage itself. The authors list six harms (53-72) that may arise from changing the definition of what a marriage is. Their argument is based on the ideas that Law tends to shape beliefs; beliefs shape behaviour; and beliefs and behaviours affect human interests and well-being (54). The particular harms identified are:

The first three parts of this series (see Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3) detailed the positive arguments made by the authors for a “conjugal” view of marriage. The remainder of the book—chapters four through six, the conclusion, and the appendix—address objections to the view that the authors have presented. The fourth chapter, “What’s the Harm?”, addresses an objection commonly put by advocates of same-sex marriage, that extending the institution to same-sex couples will increase the blessings of marriage while doing no harm to existing marriages or marriage itself. The authors list six harms (53-72) that may arise from changing the definition of what a marriage is. Their argument is based on the ideas that Law tends to shape beliefs; beliefs shape behaviour; and beliefs and behaviours affect human interests and well-being (54). The particular harms identified are:

- Redefining marriage redefines it for everyone. Opposite-sex unions would increasingly be defined by what they had in common with same-sex unions; that is, they would come to be seen primarily or even exclusively as emotional unions, and this would make the basic goods of marriage traditionally understood, more difficult to realise. For example, choosing a suitable partner might be reduced to emotional signals of compatibility rather than a prospective partner’s fitness for such prosaic things as domestic relations and parenting.

- By making marriage about emotional union, the norms of marriage make less sense. If sexual complementarity is optional, so too are permanence and exclusivity. As the norms weaken, so might the emotional and material well-being that marriage gives to spouses.

- Conjugal marriage reinforces the centrality of reproduction and parenting, and the idea that men and women bring different, complementary strengths to the tasks of parenting. As the connection between marriage and parenting is obscured, no parenting arrangement will be recognised as ideal. The problem here is not that same-sex couples cannot be excellent parents, but the development of the idea that mother or father is superfluous. The authors argue that the result will be the diminishing of the social pressures and incentives for husbands to remain with their wives and children, or for men and women to marry before having children. Ultimately, because having a loving biological father and mother is ideal for child development, many children, and so the state also, will be worse off.

- The authors suggest that moral and religious freedom will be threatened for anyone who does not agree with the new legal definition of marriage. If support for conjugal marriage is really akin to racism—as has been claimed by those supporting changes to the definition of marriage, then those who support the traditional view should be subject to similar cultural and legal treatment that racists receive.

- The revisionist view will undermine friendship and make things harder for single people. As marriage is defined simply as the most valuable or even only kind of deep communion, it becomes harder to find emotional and spiritual intimacy in nonmarital friendships.

- Finally the authors address the so-called “conservative objection” that extending marriage would impose its norms on more relationships, which can only be a good thing. This objection fails, they suggest, because the state could not effectively encourage norms for which there is no deep and rational basis. “Rather than imposing traditional norms on same-sex relationships, abolishing the conjugal view would tend to erode the basis for those norms in any relationship” (67, original emphasis).

Chapter five, “Justice and Equality” (73-81), addresses the criticisms that the conjugal view is inconsistent when dealing with infertile marriages, and at odds with the principle of equal access to marriage. The second objection is easily addressed:

Laws that distinguish marriage from other bonds will always leave some arrangements out. You cannot move an inch toward showing that marriage policy violates equality, without first showing what marriage is and why it should be recognized legally at all. That will establish which criteria (like kinship status) are relevant, and which (like race) are irrelevant to marriage policy (80-81, original emphasis).

The authors argue, as noted in an earlier post, that infertility does not invalidate a marriage, for even the infertile couple engage in an act of bodily union that is fit for and capable of reproduction even if the goal is never achieved. Further, the infertile couple demonstrate that marriage is a human and social good in itself, that marriage is more than merely reproduction. Of course a friendship between two men or two women is also valuable in itself, but “lacking the capacity for organic bodily union, it cannot be valuable specifically as a marriage; it cannot be the comprehensive union on which aptness for procreation and distinctively marital norms depend” (76, original emphasis).

Is support for the conjugal view of marriage “a cruel bargain”—the title of the sixth chapter (83-93)? Does it win support for the many at a cruel cost for the few? Why argue for a position that harms the personal fulfilment, practical interests, and social standing of same-sex-attracted people? The authors agree that same-sex couples, and indeed many other kinds of relational partnerships seeking practical legal benefits (such as recognition as next of kin, financial and medical rights, etc.) should not be hindered from obtaining them. Further, because every marriage policy will keep some people from legally recognised relationships, we must fight against arbitrary or abusive treatment of those for whom this is the case, with the same force and diligence that we use to oppose unjust distinctions by race or sex (91).

Legal recognition does not include changing the definition of marriage, however, for sheer legislative will cannot erase the very real differences between the conjugal and revisionist views of marriage, or make disregarding them harmless to the common good. “Redefining civil marriage means pretending otherwise” (87).

The same-sex civil marriage debate is not about anyone’s private behavior, but about legal recognition. … Legal recognition makes sense only where regulation does: these are inseparable. The law, which deals in generalities, can regulate only relationships with a definite structure. Such regulation is justified only where more than private interests are at stake, and where it would not obscure distinctions between bonds that the common good relies on. As we have argued, the only romantic bond that meets these criteria is marriage, conjugal marriage (90, 92).

The authors conclude, therefore, that marriage is a particular kind of union with distinct and essential features which cannot be set aside without fundamentally changing and weakening what marriage is. They make this claim on the basis of philosophical and legal considerations without appeal to religious or theological authorities. They have amassed a great deal of evidence to highlight the rationality of their arguments, and to show how and why counter-arguments fail.

Marriage is not a legal construct with totally malleable contours—it is not “just a contract.” Instead, some sexual relationships are instances of a distinctive kind of bond that has its own value and structure, which the state did not invent and has no power to redefine. As we argued in chapter 1, marriages are, like the relationship between parents and their children or between the parties to an ordinary promise, moral realities that create moral privileges and obligations between people with or without legal enforcement. Whatever practical realities draw the state into recognizing marriage in the first place (e.g. children’s needs), the state, once involved, must get marriage right to avoid obscuring the shape of this human good (80, original emphasis).

Marriage understood as the conjugal union of husband and wife really serves the good of children, the good of spouses, and the common good of society. When the arguments against this view fail, the arguments for it succeed, and the arguments against its alternative are decisive, we take this as evidence of the truth of the conjugal view. For reason is not just a debater’s tool for idly refracting positions into premises, but a lens for bringing into focus the features of human flourishing (97).

This week I have been at the 2017 ANZATS Conference in Adelaide. The theme this year has been “Kinship & Family in Contemporary Australia and New Zealand.” The two international guests have given excellent plenary addresses, and the elective sessions that I have attended have been good. Of course, one of the best things about Conferences is catching up with peers from around the country—and from New Zealand, and meeting new friends.

This week I have been at the 2017 ANZATS Conference in Adelaide. The theme this year has been “Kinship & Family in Contemporary Australia and New Zealand.” The two international guests have given excellent plenary addresses, and the elective sessions that I have attended have been good. Of course, one of the best things about Conferences is catching up with peers from around the country—and from New Zealand, and meeting new friends.