After the untimely death of her two remaining sisters, Charlotte Brontë wrote a ‘Biographical Notice of Ellis and Acton Bell’ in which she revealed that the authors of the books designated by these names—Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey—were, in fact, Emily and Anne Brontë (See Anne Brontë, Agnes Grey, Penguin Classics, lvii-lxiv). She defends her sisters from some of the criticisms they have received from reviewers. Of Anne, in particular, she writes: ‘She was a very sincere and practical Christian, but the tinge of religious melancholy communicated a sad shade to her brief, blameless life’ (lxi). Again, Anne,

After the untimely death of her two remaining sisters, Charlotte Brontë wrote a ‘Biographical Notice of Ellis and Acton Bell’ in which she revealed that the authors of the books designated by these names—Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey—were, in fact, Emily and Anne Brontë (See Anne Brontë, Agnes Grey, Penguin Classics, lvii-lxiv). She defends her sisters from some of the criticisms they have received from reviewers. Of Anne, in particular, she writes: ‘She was a very sincere and practical Christian, but the tinge of religious melancholy communicated a sad shade to her brief, blameless life’ (lxi). Again, Anne,

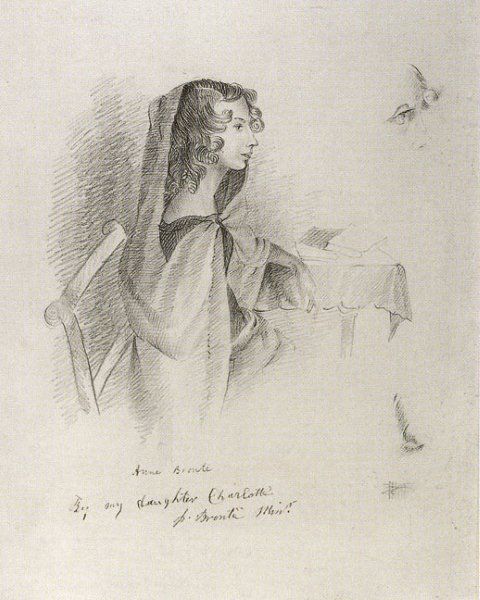

Was religious, and it was by leaning on these Christian doctrines in which she firmly believed, that she found support through her most painful journey . . . Anne’s character was milder and more subdued [than Emily’s] . . . but was well-endowed with quiet virtues of her own. Long-suffering, self-denying, reflective, and intelligent, a constitutional reserve and taciturnity placed and kept her in the shade, and covered her mind, and especially her feelings, with a sort of nun-like veil, which was rarely lifted (xliii).

Anne’s faith was both a blessing and a strength to her life, especially in the suffering that preceded her death, and also, in Charlotte’s opinion, a detriment that threw a ‘sad shade’ across her life. It is worth noting, however, that Charlotte’s second comment suggests this tendency may have arisen also on account of her ‘constitutional reserve’—her natural disposition.

It is possible, however, that Charlotte was assigning to Anne the attributes Anne ascribed to Nancy Brown in Agnes Grey. In her novel, Nancy was a widow, afflicted and incapacitated with several disabilities, whom the protagonist, Agnes, would visit.

‘Well, Nancy, how are you to-day?’

‘Why, middling, miss, i’ myseln – my eyes is no better, but I’m a deal easier i’ my mind nor I have been,’ replied she, rising to welcome me with a contented smile, which I was glad to see, for Nancy had been somewhat afflicted with religious melancholy

(Agnes Grey, 87).

The ensuing narrative makes clear that the cause of this religious melancholy was an overly-scrupulous conscience, the fruit of a moralistic approach to Scripture reinforced by a moralistic form of ministry. When the local Rector visits the poor of the parish,

He’s sure to find summut wrong, and begin a calling ’em as soon as he crosses th’ doorstuns: but may-be, he thinks it his duty like to tell ’em what’s wrong; and very oft he comes o’ purpose to reprove folk for not coming to church, or not kneeling an’ standing when other folks does, or going to th’ Methody chapel, or summut o’ that sort… (88).

The Rector is clearly more concerned with the outward performance of religious duty and convention than he is with the lives and condition of the poor folk he visits. He scorns Nancy’s spiritual fears, and accuses her of laziness and unfaithfulness. If she would simply stop making lame excuses and go to church, everything would be fine. He is entirely dismissive of her spiritual need and the reality of her physical pain and disability. How different he is from the new curate, Mr Weston, who is genuinely concerned for the spiritual and material welfare of the parishioners, who listens compassionately, and speaks and acts with kindness!

But the problem is not solely in the Rector, for Nancy herself has absorbed the moralism so pervasive in her day:

I was sore distressed, Miss Grey – thank God it’s owered now – but when I took my Bible, I could get no comfort of it at all. That very chapter ’at you’ve just been reading troubled me as much as aught – “He that loveth not, knoweth not God.” It seemed fearsome to me; for I felt that I love neither God nor man as I should do, and could not, if I tried ever so . . . And many – many others, miss; I should fair weary you out, if I was to tell them all. But all seemed to condemn me, and to show me ’at I was not in the right way (89).

Nancy seems to read the Bible as a Word that condemns, as a mirror that highlights every flaw. For her, there is no comfort in the Bible; rather, it is fearsome, demanding, condemning. The ministry of the Word and the ministry of the Church had combined to produce a ‘religious melancholy’ in her, a sense of unworthiness and despair that robbed her of faith, hope, joy, and endurance. Anne Brontë, despite her sister’s observation of her own life, is clearly rejecting this form of ministry and spirituality. Moralism—a concern for establishing one’s own moral worth by adhering to a system of morality that one accepts as necessary to be a good person acceptable to God and others—is a graceless substitute for the gospel of Christ, and produces the kind of bitter fruit seen in the self-righteous callousness of the Rector and Nancy’s spiritual despair. Moralism, both religious and secular, is a common temptation for anyone who wants to live a good life.

It is true that Scripture can convict our hearts and show us our fault. But as Martin Luther clearly counsels, we are to read the Bible as both Law and Promise. Thus, while the Bible does convict us of wrong being and doing, it also calls us out of ourselves, and beyond ourselves, to the promise of grace and forgiveness in Jesus Christ. Our worth and acceptance are grounded in him—alone! Freed from the pressure and necessity of having to establish our own moral worth and acceptability, we are freed also to hope, to rejoice, and to love others freely.

“It is good for the heart to be established by grace” (Hebrews 13:9).