Yesterday I posted a piece on Diaspora Judaism, and asked whether patterns of life in Diaspora Judaism might serve as an analogy for being the church in a post-Christian environment? There are obvious differences between the contemporary church and Diaspora Judaism, especially the fact that Diaspora Judaism was at its core, an ethnic community with common ancestry, custom and heritage. Perhaps, though, the contemporary church might learn from the success of Diaspora communities which managed to maintain their distinctive identity and faithfulness, sometimes for centuries, in the midst of a foreign and sometimes hostile environment.

Yesterday I posted a piece on Diaspora Judaism, and asked whether patterns of life in Diaspora Judaism might serve as an analogy for being the church in a post-Christian environment? There are obvious differences between the contemporary church and Diaspora Judaism, especially the fact that Diaspora Judaism was at its core, an ethnic community with common ancestry, custom and heritage. Perhaps, though, the contemporary church might learn from the success of Diaspora communities which managed to maintain their distinctive identity and faithfulness, sometimes for centuries, in the midst of a foreign and sometimes hostile environment.

Paul Trebilco identified several key features which sustained Diaspora Judaism, including their legal status within the Roman world, which offered some degree of protection from local persecution. Other features identified may offer some insight into how the church might retain its unique and distinct identity and ethos…

1. The local community

The community itself was central to life in the Diaspora. It was here that ethnic Jews found the acceptance, identity, value, friendship and support they needed to live faithfully in foreign and sometimes hostile environments. Community life included weekly gatherings, regular feast and fast days, and financial contributions, all of which helped reinforce their distinctive identity and lifestyle, and bond them together in solidarity.

Trebilco emphasises the social significance of the local community and weekly gatherings. It is, perhaps, this aspect of community life which is more difficult to nurture in a post-Christian context. Majority-culture Christians are typically highly assimilated with so many relational opportunities, that participation in the local Christian community loses its impetus and value. We simply do not need the community the way the Diaspora Jews often did. One strategy to alter this circumstance is to intentionally nurture the relational and social aspects of community life, so that genuine friendships and supportive relationships might occur. More important is the fundamental shift of one’s core identity to being essentially Christian. If being a Christian is our core identity, we will more naturally gravitate toward and value the community.

2. Endogamous Marriage, Parenting and Re-socialisation

Diaspora Jews by and large married within their own ethnic group, and raised their children as Jews, passing on Jewish traditions and heritage from generation to generation. Proselytes and others seeking entry into the community were re-socialised, learning the ways of the community and adopting them as their own.

I don’t know how easily these could inform contemporary Christianity. When I married it was almost assumed that a Christian would marry another similar-brand Christian. I am not sure that is still the case, especially for Christian women, for whom the options are often quite limited. This key feature of Diaspora Judaism points to the necessity of ministries that support and nurture marriage and family life, including the raising of children in an environment of active faithfulness. I suspect this will become increasingly important as marriages and families continue to suffer the stress and breakdown which characterises the contemporary West. I suspect that it will also become an important aspect of Christian witness.

The ancient church had a strong tradition of re-socialisation: new converts received extensive mentoring and catechesis before finally being baptised and accepted into the full life of the community. This period of instruction and training was designed to help converts learn and adopt the beliefs and practices which sustained the community in the midst of the hostile Roman empire. Many voices are calling for a restoration of such practices in the church today.

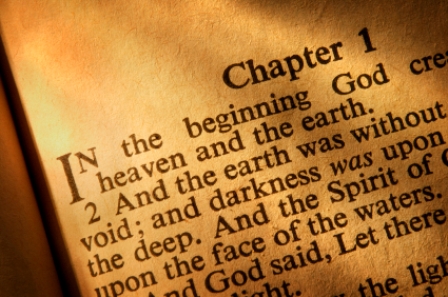

3. The Torah

Regular instruction in the Law was a key element in the weekly synagogue and laid the foundations of Diaspora identity. Trebilco makes the interesting observation that Moses was seen as a “skilful lawgiver, a profound philosopher, a noble king, a supreme military commander, miracle worker and priest” (298). This indicates to some degree, the assimilation of teaching to categories of thought common in the surrounding culture.

The more important observation, of course, concerns the centrality of Scripture to identity, community and life formation. Personal and communal transformation requires extensive and intensive engagement with the texts of Scripture, learning together to inhabit the world of the biblical text, and to embody that world in the daily realities of life.

4. Visible Practices

Trebilco identifies the importance of Jewish dietary laws, Sabbath-keeping and circumcision as “key boundary markers of Jewish identity, with great social significance” (298). The first two, in particular, were highly visible commitments which distinguished Diaspora Jews from their countrymen, and reinforced their distinctive identity. The third, perhaps visible in the context of public baths, constituted, says Trebilco, a strong affirmation of Jewish identity for men. I find the visibility of the Diaspora community intriguing.

Perhaps the closest analogue to these practices for the contemporary church is gathering for public worship, followed closely by practices of gathering for common meals. Other practices could be such things as serving the poor or other good works in the public sphere. In any event, visible identification with the cause of Christ will effectively enhance one’s core sense of Christian identity.

5. The Fundamental Commitment

Finally, Trebilco notes the fundamental belief which underlies the entire structure of Diaspora Judaism, including even the core reality of ethnicity: monotheist belief in the one God of Israel, whose people they are. Belief that this God was the “God of Israel” implicated them ethnically. Belief in the one God entailed the rejection of all other so-called gods, idols and cults.

In the post-Christian environment in which we now live the church will continue so long as there are people whose identity is grounded in the reality of the divine grace by which we have been chosen and called, that is, those whose our existence is a response to this God who has given himself to us in Jesus Christ. An essential difference also emerges here: Diaspora Judaism was inherently an ethnic community; with the revelation of God in Christ, we understand God in universal terms and not simply as God of the Jews only. Diaspora Judaism grew by procreation and occasional proselytes. The Christian community is commanded to make disciples and so to grow by conversion as well as by procreation. It is a Diaspora community characterised by mission.