Today I am speaking at Lesmurdie Baptist Church—my old stomping ground… The church and congregation hold a special place in my life; I was pastor of the church for five years, and an ordinary member for another two years, and in that time grew to love the people and the pastoral team with whom I worked. It is always a privilege and a joy to return. My topic for today is: “If We Only Knew: From Academia to Application.” My brief is to bring something from the world of academia which might otherwise take years to filter down into congregational awareness and life. I love the fact that senior minister, Karen Siggins, wants her congregation to be informed concerning important developments and trends in contemporary theology: may her tribe increase! She and the pastoral team have devoted the whole month to this series.

Today I am speaking at Lesmurdie Baptist Church—my old stomping ground… The church and congregation hold a special place in my life; I was pastor of the church for five years, and an ordinary member for another two years, and in that time grew to love the people and the pastoral team with whom I worked. It is always a privilege and a joy to return. My topic for today is: “If We Only Knew: From Academia to Application.” My brief is to bring something from the world of academia which might otherwise take years to filter down into congregational awareness and life. I love the fact that senior minister, Karen Siggins, wants her congregation to be informed concerning important developments and trends in contemporary theology: may her tribe increase! She and the pastoral team have devoted the whole month to this series.

I have chosen as my theme a topic completely out of my comfort zone: the relation between science and theology, and exploring the particular issue presently experiencing vigorous debate in Evangelical theology—the historicity or otherwise of Adam. Here is the outline…

*****

My own awareness of these issues has been stimulated by a BBC production The Incredible Human Journey and by the work of the Human Genome project. I recognised almost immediately that both these scientific projects would issue a great challenge to Evangelical Christianity. I was right. In the next few years a debate arose in evangelicalism around the historicity of Adam and Eve: did Adam and Eve really exist? Two books from evangelical biblical scholars spotlight the issue: C. J. Collins’ Did Adam and Eve Really Exist and Peter Enns’ The Evolution of Adam. As you can guess, the two books took opposing positions with respect to this question.

Of course, serious theological questions arise around this issue: not least the issues raised by common interpretation of Romans 5:12-21.

Human Origins: How did we come to be here?

Human Origins: How did we come to be here?

In the modern era many answer that question with the word evolution. Some Christians accept evolution as fact. Others reject it out of hand, and insist on a literal six-day creation by divine fiat. Still others adopt a position of theistic evolution. Francis Collins, director of the Human Genome Project, is not comfortable with the term theistic evolution and prefers simply to speak of evolution by itself. Yet, as a committed Christian, Collins believes that God being almighty and all-knowing pre-loaded the evolutionary process so that it would result in his intended purpose.

Science and Faith: Must the relation be conflictual?

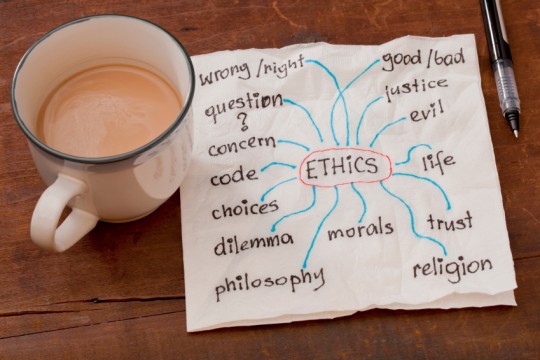

This issue raises the perennial question of the relation between science and faith. On the one hand, in the modern west science has achieved a kind of cultural status as the arbiter and final authority of truth and wisdom. That which is not ‘scientific’ is intellectually and possibly, morally, suspect. Yet Christians—and not only Christians—claim that there are other sources of truth and wisdom, the Bible in particular. How, then, are Christians to respond when it seems that science and faith come into conflict?

The response of liberal theology to that question was simply to re-interpret or even jettison those parts of the Bible which conflicted with scientific discoveries; they gave science the priority. Other Christians adopted a defensive posture, ignoring or attacking the science, or else developing their own supposedly ‘scientific’ programmes to insist that the Bible teaches precise and actual scientific knowledge, with the result that ‘true science’ agrees with the Bible. If it does not agree with the Bible it is not ‘true’ science.

A major part of the issue, however, concerns the question of biblical interpretation. Sometimes Christians fail to recognise that what we think is the teaching of the Bible is in fact our interpretation of the Bible, and the reality that the Bible can be and is interpreted in different ways by believers who are equally committed to a high-view of Scripture. And so the question comes to us: Can we be open to new ways of interpreting familiar

passages? And can we look for ways of interpretation that maximise the possibility of finding common ground between science and faith without compromising what we consider to be essential theological convictions? Note, here, Augustine’s wisdom:

In matters that are so obscure and far beyond our vision, we find in Holy Scripture passages which can be interpreted in very different ways without prejudice to the faith we have received. In such cases, we should not rush in headlong and so firmly take our stand on one side that if further progress in the search for truth justly undermines this position, we too fall with it (cited in Collins, “The Language of God,” in Metaxas, Socrates in the City, 317).

Two Interpretive Moves

I want to suggest two interpretative moves that will assist us as we think about this particular issue. First, Millard Erickson’s view of progressive creationism. Erickson argues that God uses both the processive mechanism of micro-evolution—evolution within a particular species, and de novo creative events. There may well have been ‘pre-human’ creatures prior to the creation of Adam and Eve, but Adam and Eve were a fresh creative work of God (Erickson, Christian Theology 3rd ed., 446).

I note also, that Francis Collins, despite his insistence that God pre-loaded the evolutionary mechanism, also speaks of God ‘gifting’ humanity with ‘the knowledge of good and evil (that’s the moral law), with free will, and with an immortal soul. And Homo sapiens became Homo divinus’ (Collins, in Metaxas, 315). This sounds very much like a direct intervention to me.

The second interpretative move involves ‘re-thinking’ of Genesis 1:31: must God’s ‘very  good’ be understood in terms of some kind of metaphysical perfection, or might it be understood in terms of the value God the Creator places upon his work? English theologian Colin Gunton suggested that, “Rather like a work of art, creation is a project, something God wills for its own sake and not because he has need of it” (Colin E. Gunton, “The Doctrine of Creation,” in The Cambridge Companion to Christian Doctrine, 142). Such an interpretation suggests that God’s work of creation was not the end of his purpose, but the beginning of a project playing out across history and moving toward a divine purpose and climax. In this view, the immanent God accompanies his creation, at times doing new things, providentially guiding the creation toward his appointed goals.

good’ be understood in terms of some kind of metaphysical perfection, or might it be understood in terms of the value God the Creator places upon his work? English theologian Colin Gunton suggested that, “Rather like a work of art, creation is a project, something God wills for its own sake and not because he has need of it” (Colin E. Gunton, “The Doctrine of Creation,” in The Cambridge Companion to Christian Doctrine, 142). Such an interpretation suggests that God’s work of creation was not the end of his purpose, but the beginning of a project playing out across history and moving toward a divine purpose and climax. In this view, the immanent God accompanies his creation, at times doing new things, providentially guiding the creation toward his appointed goals.

These two interpretive moves may help us find a place of common ground between contemporary science and biblical faith. The fact that we share 96%+ of our DNA with chimpanzees, the fossil record of pre-modern humanoids creatures, the idea that the complexity of the human genome requires a beginning population of not two but many thousands—all these and more may be addressed within this interpretive framework. Nor does this require the story of Adam & Eve to be a fictional story. Christians may still argue that God ‘instilled’ this distinctively human nature and spirit into an original couple so they were not simply pre-modern humanoids but ‘new creatures.’

But what about death? Does not this interpretation undermine the biblical teaching that sin entered the world through one man and death through sin? Not necessarily. It may be permissible to interpret death strictly as spiritual death, both in Genesis 2:17 and Romans 5:12. Adam & Eve died when they ate the fruit—but not physically. Prior to this special creation physical death was in the world but not spiritual death for God had not created the earlier creatures as spiritual beings in the same way as modern humans have been created.

Further benefits of ‘re-thinking’ our interpretation of Scripture include a greater awareness of our natural solidarity with other creatures, especially the animal kingdom, and so of our responsibility for their care. If God’s creation is God’s project, and God has created us in the divine image, it speaks to God’s intent that we participate in this project, that we ‘play’ and ‘paint’ with him, as it were, actively taking our place and playing our part in building the kind of world that God always intended, aiming always at the festivity and shalom of the Sabbath rest which is the climax of the first creation narrative.

Last week we studied the first six verses of this psalm

Last week we studied the first six verses of this psalm