The first thing to be said about this psalm is that it is quite possible, even likely, that it should be read with Psalm 10 as a single psalm. The two psalms seem to be an acrostic poem where each line or section begins with the next letter of the alphabet. Psalm 9 starts with the first Hebrew letter, aleph, and concludes with the eleventh letter Kaph – half way through the twenty-two letter alphabet. Psalm 10 then commences with the twelfth letter Lamedh and continues to the end of the alphabet. The pattern is not entire, however; Psalm 9 for instance, omits the fourth letter Daleth, and there are a few difficulties with the pattern in Psalm 10. Nevertheless, Hebrew scholars feel there are good grounds for considering that two psalms should be read together, if not as a single work.

The vision and theme of the psalm is of the Lord as the sovereign ruler and judge of all nations. That is, the Lord is the universal sovereign who exercises judgement both for David in his immediate situation, and eschatologically for the whole world. The psalm contrasts the kingdoms of this world – the nations – with the kingdom of God. In New Testament language we might say that the whole psalm breathes the second petition of the Lord’s Prayer: Thy Kingdom come!

Verses 1-2 commence as a vow of praise to God Most High (cf. 7:17). Then follows a celebration of God’s judgement of David’s enemies, resulting in their complete and utter ruin (vv. 3-6). They are blotted out and destroyed forever, so that even the very memory of them has perished. In terms of modern sensibilities, this is very troubling indeed, for it seems that the psalmist has co-opted God for his own nationalist purposes, and provides religious validation for violence and hatred of enemies. He is, as usually we all are, convinced of the justness of his own cause, and sees his victory as divine justice.

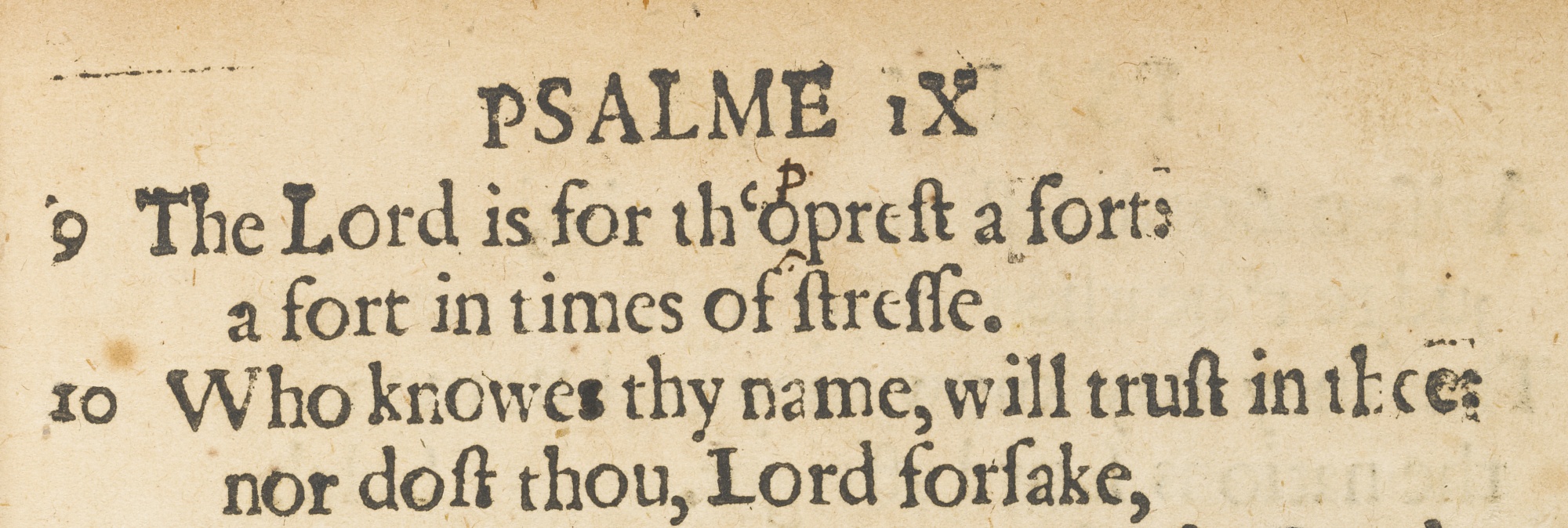

In contrast to the transience of the enemies who have perished, the Lord abides forever. In verses 7-10 David enlarges his vision: not only has God judged in his favour, but he will judge the world in righteousness and with equity. This is an unusual equity, however, for it favours the oppressed and troubled. Verses nine and ten particularly, recall Psalm 2:12, that those who seek refuge in God will not be forgotten or forsaken by God, but rather will be the recipients of his protection and blessing. For many centuries God’s people have found comfort and strength in these verses.

On the basis of this hope, then, the psalmist exhorts his listeners to praise (v. 11) and again reiterates that God does not forget the afflicted, but indeed will require or avenge their blood (v. 12). Here again modern sensibilities are affronted; yet the image serves to emphasise the reality and strictness of the divine judgement. God himself will take the cause of the afflicted and oppressed and will visit upon those who oppress them, the same kind of treatment that they have dealt out to others. Verses 13-14 now petition the Lord for his grace (cf. 4:4; 6:2), and anticipate that he shall indeed be gracious.

On the basis of this hope, then, the psalmist exhorts his listeners to praise (v. 11) and again reiterates that God does not forget the afflicted, but indeed will require or avenge their blood (v. 12). Here again modern sensibilities are affronted; yet the image serves to emphasise the reality and strictness of the divine judgement. God himself will take the cause of the afflicted and oppressed and will visit upon those who oppress them, the same kind of treatment that they have dealt out to others. Verses 13-14 now petition the Lord for his grace (cf. 4:4; 6:2), and anticipate that he shall indeed be gracious.

Verse 15 returns to the theme of judgement, and begins with an observation that the nations get caught in their own traps and devices. Like Psalm 7:15-16, this verse suggests that there is a natural moral order functioning in the world, a ‘law’ as it were, of sowing and reaping in which evil intended for others returns upon one’s own head. However, verse 16 suggests that even the apparently impersonal consequences of one’s actions are the direct result of Yahweh’s personal exercise of judgement. Verses 17-18 play on the idea of memory and forgetfulness. The wicked who forget God will ‘return’ to Sheol – where there is no memory of God (cf. 6:5). But the poor and afflicted will not be forgotten, for God remembers them and does not forget their cry (v. 12).

The final two verses of the psalm form its climax, and are the key to its meaning as a whole:

Arise, O Lord, do not let man prevail;

Let the nations be judged before you.

Put them in fear, O Lord;

Let the nations know that they are but men.

After the celebration of humanity’s exalted status in Psalm 8, this plaintive cry brings us back to earth, reminding us of our fallen state and its moral consequences. There is a stark contrast between God and humanity, between human activity and divine justice. There is also a very sharp reminder that we need divine judgement if ultimately, there is to be justice and equity.

It seems that human power will always exert itself against God, bringing injustice and oppression to others. The nations forget God (v. 17) and oppress the needy (v. 18). They rage and imagine vain things (2:1). The nations and their leaders strut about upon the stage of history as though they were God. For the psalmist, then, the only hope for peace and equity lies in the hope that God will ultimately judge the nations and thereby bring true justice to pass.

In all this, of course, a genuine problem arises: it is difficult to perceive God’s sovereign reign over the nations in our present world. Injustice, human pretension and violence abound. Where are you Lord, in the midst of the ever-present tensions within and among the nations? How long, O Lord, will you allow the powerful to oppress the poor and vulnerable? Why do you delay in coming? Arise O Lord!

We, like the psalmist, are called to see what cannot be seen: the universal sovereignty of God. And to believe what is almost impossible to believe: that God will one day put things to rights. In so doing, our hope is wholly placed on God, his faithfulness, his righteousness and his kingdom. And so we pray, Thy Kingdom come!