In her The Roots of the Reformation Gillian Evans devoted many pages detailing the recovery of the biblical languages by the Renaissance and Christian humanists which played a decisive role in the Reformation. Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494) claimed that Hebraei bibunt fontem, Graeci rivos, Latini paludes—“the Hebrews drank from the spring, the Greeks from a river, the Latins from a swamp” (Evans, Roots, 264).

In her The Roots of the Reformation Gillian Evans devoted many pages detailing the recovery of the biblical languages by the Renaissance and Christian humanists which played a decisive role in the Reformation. Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494) claimed that Hebraei bibunt fontem, Graeci rivos, Latini paludes—“the Hebrews drank from the spring, the Greeks from a river, the Latins from a swamp” (Evans, Roots, 264).

For a thousand years Western Christianity had relied on the Latin Vulgate and the numerous commentaries and glosses that had arisen around that translation. Copyist errors, traditional and philosophical interpretations, and certain translational decisions by Jerome in the fourth century all muddied the waters of biblical interpretation. Hence the humanist and Reformation cry, Ad fontes!—“Back to the sources!”

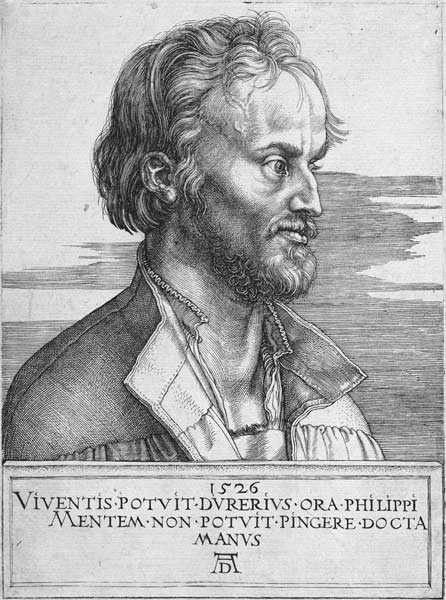

One of the Reformers, Philipp Melanchthon insisted that learning the biblical languages was essential:

Led by the Holy Spirit, but accompanied by humanist studies, one should proceed to theology . . . but since the Bible is written in part in Hebrew and in part in Greek—as Latinists we drink from the stream of both—we must learn these languages, unless we want to be “silent persons” (Evans, 264).

Likewise Martin Luther, according to biographer Scott Hendrix:

Erasmus need not have worried that Protestant reformers would destroy good scholarship. All the leading reformers were trained in the classics and most had earned advanced degrees. They had no intention of abolishing the study of Greek, Hebrew, and Latin, since the knowledge of those languages helped to make the reformation possible. Writing to a familiar supporter in 1523 Luther emphasized that point:

“Do not worry that we Germans are becoming more barbarous than ever before or that our theology causes a decline in learning. Certain people are often afraid when there is nothing to fear. I am convinced that without humanist studies untainted theology cannot exist, and that has proven true. When humanist studies declined and lay prostrate, theology was also neglected and lay in ruin. There has never been a great revelation of God’s word unless God has first prepared the way by the rise and flourishing of languages and learning, as if these were the forerunners of theology as John the Baptist was for Christ” (Hendrix, Martin Luther: Visionary Reformer, 169).

Luther’s final sentence is well worth considering. I have often repeated to my students a comment my former Greek professor made to me: “If you can learn to read the Scriptures in the original languages you will gain 20-25% additional insight into the text.”