In previous posts I have examined Romans 3:21-26, discussing views of the passage by Cranfield, Moo, and Carson. In general, they see Paul describing a new situation in which God grants to those human beings who believe in Jesus Christ, the gift of righteousness—right relationship with God—on the basis of Jesus’ sacrificial death. In this death, God himself is vindicated as righteous, and revealed as the one who justifies sinful humanity through the death of Christ.

N. T. Wright’s comment on these verses retains a number of these features but does so with a different framework of understanding. For Wright, God’s answer to the problem of Adamic humanity so graphically portrayed by Paul in 1:18 – 3:20 is the covenant with Abraham, the promise of a new, worldwide, forgiven family (Wright, “Romans” in The New Interpreter’s Bible, Volume 10, 465). Through Abraham and his descendants God intended a human faithfulness that responded to his own faithfulness, and which issued in a renewed and genuine humanity, freed from the cruel distortions of idolatry and sin (466). This new family would be heir to the world, according to Romans 4:13. Israel, however, failed in their role to offer this faithfulness to God.

Jesus’ achievement is thus to have done what Israel should have done but failed to do. He has been the light of the world, the one through whom God’s saving purpose has been revealed. Through him God has at last dealt with the sin of the world, the purpose for which the covenant was made. … The Messiah’s “obedience unto death” is the critical act—an act of Jesus, and also in Paul’s eyes an act of God—through which sins are dealt with, justification is assured, and the worldwide covenant family is brought into being (467).

In this passage, Wright argues, Paul shows that God has fulfilled his covenant promises to Abraham through the faithful obedience of Jesus Christ, thus accomplishing his covenant purpose of putting “the world to rights” (465). Wright reads the pistis Iēsou Christou (“faith in Jesus Christ”) of verse 22, and other references to faith in this passage, as a subjective rather than objective genitive—the “faith (faithfulness) of Jesus Christ” rather than “faith in Jesus Christ.” Thus, God’s righteousness is revealed in the obedient faithfulness of Jesus in which Jesus offers to God that which Israel denied (470).

Wright approaches this passage by means of this over-arching framework. As such, God’s righteousness in verse 21 is not the righteousness of God given to believers who have faith in Jesus Christ, nor the divine attribute by which God is just and justly judges sin, but the demonstration that God is righteous—that is, faithful to the promises made to Abraham. God has acted righteously by keeping his promise to Abraham.

Nevertheless, God is also the righteous Judge who must punish sins as they deserve, which he accomplishes through the death of Jesus (467, 473). Jesus’ death is presented by Paul in sacrificial terms, recalling Leviticus 16 and the Day of Atonement. He is the hilastērion—the mercy seat, or place “where the holy God and sinful Israel meet in such a way that Israel, rather than being judged, receives atonement” (474). When Wright unpacks this further, however, he appeals not to Leviticus 16, but to the Maccabean martyrs in Second Maccabees, and ultimately to the fourth Servant Song of Isaiah (Isaiah 52:13-53:12):

The sacrificial language of 3:25, used in connection with the violent death of a righteous Jew at the hands of pagans, makes sense within the context of the current martyr stories; but those martyr stories themselves send us back, by various routes, to Isaiah 40-55; and when we get there we find just those themes that we find in Romans 3 (475).

Still, he insists that “the lexical history of the word hilastērion is sufficiently flexible to admit of particular nuances in different contexts” (476), so that it refers not only to Jesus’ death as the place of atonement, but includes ideas of propitiation and expiation as well. That is, Jesus’ death deals effectively with sin both by averting God’s wrath and by cleansing human sin.

Just as the mercy-seat fulfilled its function when sprinkled with sacrificial blood, so Paul sees the blood of Jesus as actually instrumental in bringing about that meeting of grace and helplessness, of forgiveness and sin, that occurred on the cross. Once again, the sacrificial imagery points beyond the cult to the reality of God’s self-giving act in Jesus (476-477).

I continue to have questions about the way in which Wright sets up his covenantal framework, and consequently, with his approach to justification. Nevertheless, Wright’s account of how the death of Jesus works to secure the salvation of sinners agrees in its central claims with those treatments of the topic by Cranfield, Moo, and Carson, despite his evident attempt to distance himself from too juridical a treatment of the cross.

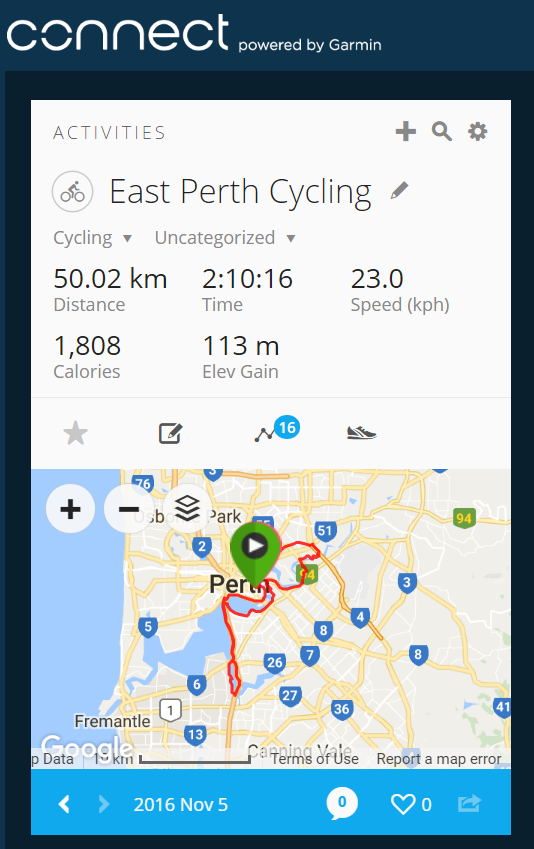

On Saturday I went for my longest ride so far—at least since I have been recording my rides. I do remember riding two-and-a-half hours a couple of times on my old bike, and even three hours once, so perhaps I rode 50K then. Or not. In any case, I have been recording my rides for the last six to eight months, since I have been using my new bike—an entry-level racer. Prior to that, I had a good hybrid bike that I really enjoyed, but it was stolen. It took me almost six months to save for the new one.

On Saturday I went for my longest ride so far—at least since I have been recording my rides. I do remember riding two-and-a-half hours a couple of times on my old bike, and even three hours once, so perhaps I rode 50K then. Or not. In any case, I have been recording my rides for the last six to eight months, since I have been using my new bike—an entry-level racer. Prior to that, I had a good hybrid bike that I really enjoyed, but it was stolen. It took me almost six months to save for the new one.