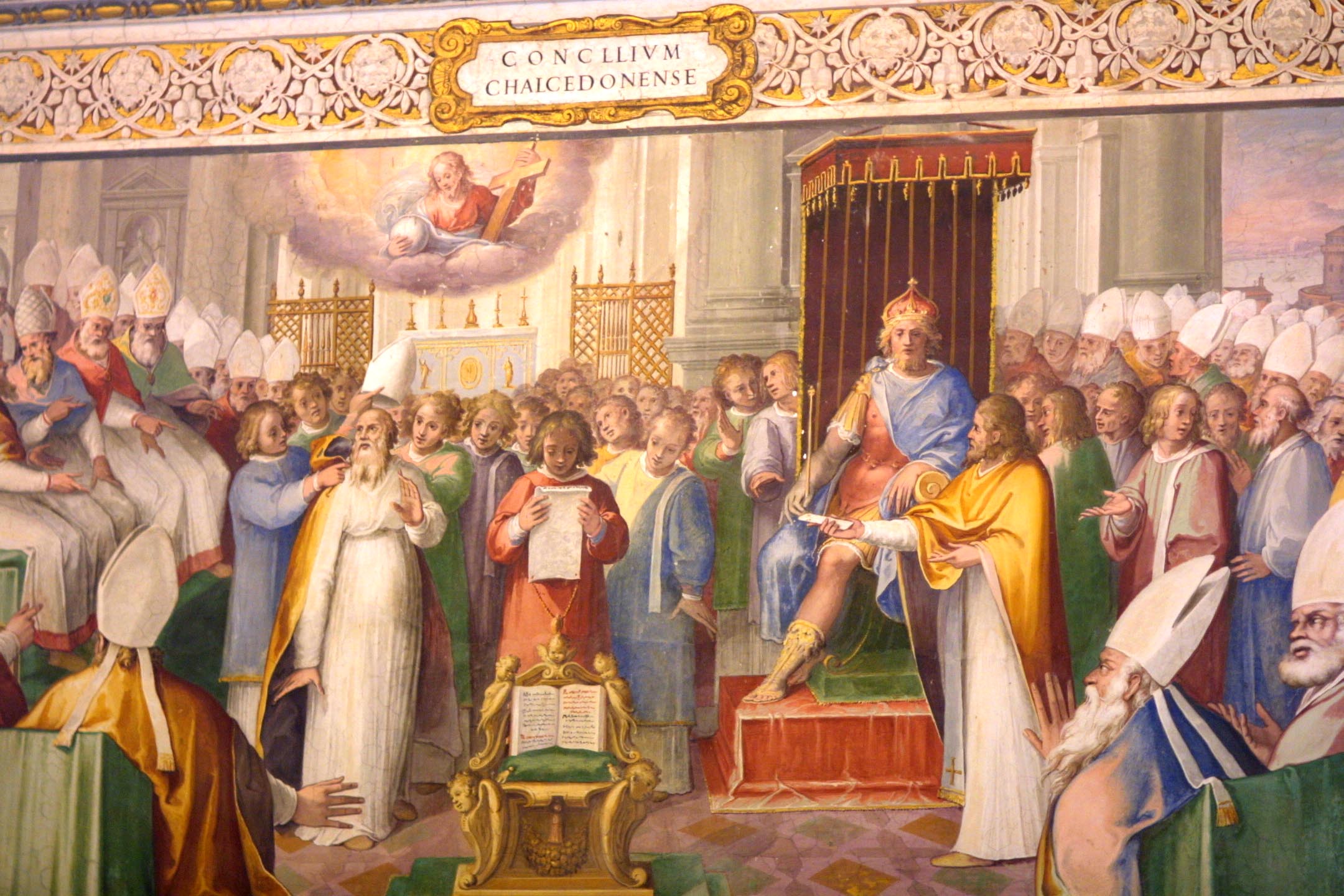

The Council of Chalcedon in 451 is one of the milestones of Christian theology where the church sought to understand the relation between the deity and the humanity of Jesus Christ. In its famous Definition, the Council affirmed its faith as follows:

The Council of Chalcedon in 451 is one of the milestones of Christian theology where the church sought to understand the relation between the deity and the humanity of Jesus Christ. In its famous Definition, the Council affirmed its faith as follows:

We, then, following the holy Fathers, all with one consent, teach people to confess one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, the same perfect in Godhead and also perfect in manhood; truly God and truly man, of a reasonable [rational] soul and body; consubstantial [co-essential] with the Father according to the Godhead, and consubstantial with us according to the Manhood; in all things like unto us, without sin; begotten before all ages of the Father according to the Godhead, and in these latter days, for us and for our salvation, born of the Virgin Mary, the Mother of God, according to the Manhood; one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, only begotten, to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably; the distinction of natures being by no means taken away by the union, but rather the property of each nature being preserved, and concurring in one Person and one Subsistence , not parted or divided into two persons, but one and the same Son, and only begotten God , the Word, the Lord Jesus Christ; as the prophets from the beginning [have declared] concerning Him, and the Lord Jesus Christ Himself has taught us, and the Creed of the holy Fathers has handed down to us.

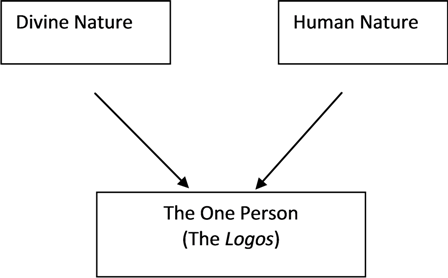

Bruce McCormack unpacks the achievement and significance of the christology of Chalcedon as “two natures in one person,” with the person being identified as God. He depicts the form as Chalcedonian christology as follows:

The diagram shows that the two

natures coming together to form the

one person, but that person is identified with the person of the Logos. As such, the Logos is the acting subject of the union and the human nature of Jesus, although real, plays no active role in the work of Christ.[1]

The main problem, for McCormack, is that Chalcedon remains ambiguous, open to both Apollinarian and Nestorian distortions. One the one hand, the Alexandrian christology which won the day at Chalcedon, while rejecting Apollinarianism, still proposed a way of understanding the person of Christ in which the Logos was the acting subject, and the humanity of Jesus a passive instrument in his hands.

The heart of [Apollinarian Christology] lay rather in…the drive to understand the Logos as the ruling principle of Christ’s human nature. Apollinarius’s own way of achieving that end—through the notion that the Logos simply takes the place of the human mind (nous)—was rather crude. A more sophisticated way of achieving the same goal would be through the affirmation of a “communication” between the divine nature and the human nature such that it becomes reasonable to think of the Logos as acting upon his human nature. In both cases, the human nature is reduced to the status of a passive instrument in the hands of the Logos; it is the object upon which the Logos acts. Against this tendency it has to be said that if the mind and will that are proper to Christ’s human nature do not cooperate fully and freely in every work of the God-human, then Christ’s humanity was not full and complete after all.[2]

On the other side, theologians for centuries have divided between the natures—in opposition to Chalcedon—parcelling out the work of Christ in such a way that some work is attributed to the divine nature and some to the human nature. This means for McCormack that “the ‘natures’ were made ‘subjects’ in their own right. The singularity of the subject of these natures was lost to view—and with that, the unity of the work.”[3] The reason for this widespread tendency is the hold that the concept of divine immutability has had on theology since ancient times. “It was unthinkable for the ancients that God could suffer and die. Only a human was believed able to do that. Confronted by theopaschitism, even the most Cyriline theologian often turns into a Nestorian.”[4]

However contrary they are with respect to their results, both of the tendencies we have examined—the tendency toward Apollinarianism resident in the thought that the Logos is the operative agent who achieves redemption in and through his human nature, as well as the tendency toward Nestorianism generated by the flight from a mutable God—have the same source. Their source is a process of thought that abstracts the Logos from his human nature in order, by turns, now to make of the human nature something to be acted upon by the Logos and now to make of that nature a subject in its own right in order to seal the Logos off hermetically from all that befalls that human nature from without. In both cases, the Logos is abstracted from the human nature he assumed…[5]

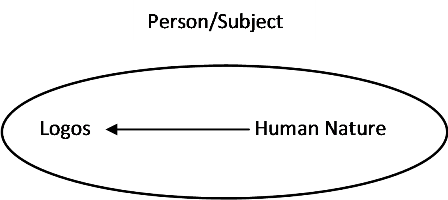

That is, the subject of the person of Jesus is understood as the Logos, rather than the God-human in his divine-human unity. Thus McCormack proposes a different way to understand the person of Jesus Christ:

In this portrayal, the person stands outside

and above the two natures as it were,

so the person is not aligned with the Logos,

but with the man Jesus Christ in his

divine-human unity. The arrow indicates

that there is a communication to the divine nature of that which belongs to the human nature. That is, the acts and experiences of the human nature are also experienced by the Logos in his union with the human nature, so that as Jesus suffers and dies, he does not do simply simply in his human nature, as such. Jesus Christ in his divine-human unity suffers and dies, and the Logos experiences this suffering and death instead of being sheltered from it. In this way suffering and death are taken up into the very life of God so that God takes upon himself in the person of the Incarnate, the suffering and death that properly belongs to humanity.

*****

[1] McCormack, Bruce L., “The Ontological Presuppositions of Barth’s Doctrine of Atonement,” in The Glory of the Atonement: Biblical, Theological & Practical Perspectives, ed. Hill, Charles E. & Frank A. James, (Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Press, 2004), 350.

[2] McCormack, “Ontological Presuppositions,” 352-353.

[3] McCormack, “Ontological Presuppositions,” 354.

[4] McCormack, “Ontological Presuppositions,” 355.

[5] McCormack, “Ontological Presuppositions,” 355.