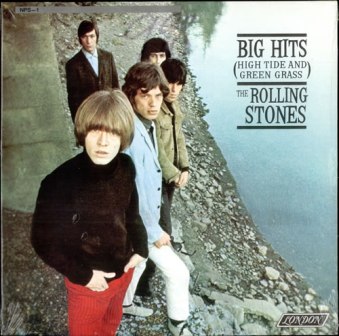

The heroes of my adolescence were in town and on the news all last week. I was introduced to the Stones when I was about eight or nine years old and my elder brother came home with “Top of the Pops 1969.” Tracks I remember include the Beatles Ob-La-Di, CCR Green River, Elvis In the Ghetto, Thunderclap Newman Something in the Air, Peter Sarstedt Where Do You Go To My Lovely? and The Archies Sugar, Sugar. My favourite track was probably Elvis in those days, but I was intrigued by the cowbell at the start of Honky Tonk Women. Soon after my brother bought High Tide and Green Grass and I was hooked—on the music, not the grass—I always wondered, in those days, what on earth the title meant. Nevertheless, Little Red Rooster, Satisfaction, Get Off of My Cloud, As Tears Go By, Paint it Black…somehow the music worked its way into my soul. As did the band.

The heroes of my adolescence were in town and on the news all last week. I was introduced to the Stones when I was about eight or nine years old and my elder brother came home with “Top of the Pops 1969.” Tracks I remember include the Beatles Ob-La-Di, CCR Green River, Elvis In the Ghetto, Thunderclap Newman Something in the Air, Peter Sarstedt Where Do You Go To My Lovely? and The Archies Sugar, Sugar. My favourite track was probably Elvis in those days, but I was intrigued by the cowbell at the start of Honky Tonk Women. Soon after my brother bought High Tide and Green Grass and I was hooked—on the music, not the grass—I always wondered, in those days, what on earth the title meant. Nevertheless, Little Red Rooster, Satisfaction, Get Off of My Cloud, As Tears Go By, Paint it Black…somehow the music worked its way into my soul. As did the band.

This week, of course, has been tragic for them, for Mick Jagger particularly. The death of his long time partner L’Wren Scott has rocked his world, not in the usual sense. I have read a fair bit of the coverage and came across a quote which led me to an old New York Times Magazine article. Speaking, at that time, about his relationship with L’Wren, Mick said, “I don’t really subscribe to a completely normal view of what relationships should be,” he says. “I have a bit more of a bohemian view.”[1] We probably all know what he means.

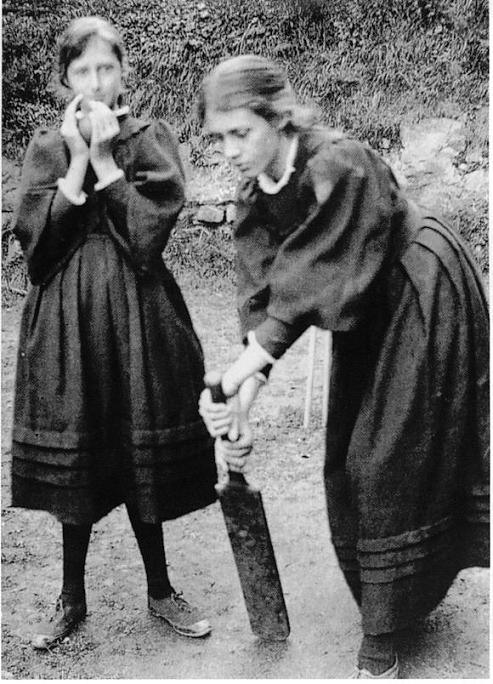

But I was interested. Recently, in our Christian Worldview class, we watched a short segment on early English Bohemians from Alain De Botton’s Status Anxiety.[2] He toured Charleston, the home of the “Bloomsbury Group” in the 1920 and 30s who experimented with new forms of lifestyle. It was the home of author and artist Vanessa Bell, sister of Virginia Woolf. De Botton describes Bohemia as “a way of looking at the world; Bohemia is not a place, it is a state of mind. And what that state of mind boils down to is a sense of independence and freedom, a commitment to live by your own values.” He suggests that it was a “secular replacement for Christianity in a time when Christianity was waning.” It provided a spiritual rather than material way of evaluating ourselves.

De Botton’s explanation is both helpful and unhelpful. He is helpful when describing the Bohemian state of mind, and correct in identifying it as “secular.” He is less than helpful in describing Bohemia as “spiritual.” He uses the term in contrast to material or external modes of thought, and thereby emphasises the internal motivations and disposition of those who practice a Bohemian lifestyle. We should note that this kind of interiority has nothing to do with biblical forms of spirituality. When Paul speaks of those who are “spiritual” (e.g. 1 Corinthians 2:15), he invariably means those whose lives are under the influence and direction of the Holy Spirit. This, of course, is utterly distinct from a self-generated sense of independence and freedom, or a commitment to live by one’s own values.

De Botton interviewed Vanessa Bell’s granddaughter, Virginia Nicholson, who said that the Bloomsbury Group “believed in truth, true living and true loving. They rejected the bourgeois values of the age, and everything the bourgeoisie stood for. … Experimentation was of the essence here. It was about breaking the rules and giving themselves a sense of validation by doing that.” She suggested we should be grateful for the way in which her forebears broke through stultifying traditions so that we enjoy the kinds of social freedoms we take for granted today. “In a curious way,” she said, “We are all bohemians now.”

What do you think: Are we all Bohemians now?

In many ways Virginia Nicholson is right: we are all bohemians now, those of us, at least, who live in western liberal democracies. Perhaps not to the extent of the Bloomsbury Group or Mick Jagger, but bohemian nonetheless. Bohemian values have gone mainstream, so that our culture too, believes in truth, true living and true loving, so long as this is understood as being true to oneself. The sexual and interpersonal experimentation that lay close to the centre of the Bloomsbury experiment is widespread and accepted today, encouraged as a means of personal fulfilment and discovery. The self has become the centre of value.

Perhaps Nicholson’s most telling phrase is “giving themselves a sense of validation.” Bohemia was indeed a secular replacement for Christianity, though not in the way De Botton thinks. At the heart of Christian faith is justification, freely offered on the basis of the saving death of Jesus. This is divine validation given by God to those who turn to God through Jesus Christ in humble and repentant faith. To be justified is to be forgiven, accepted by and restored to God, and granted a new status before God and all creation. Justification addresses the deepest and most fundamental of human needs: right relationship with God, and then consequently, with self and with others. That Bohemians would seek to validate themselves is indicative of the depth of this sense of need in the human psyche.

The bourgeoisie and the Bohemians both sought validation, the bourgeoisie through their respectability, the Bohemians through their defiance of respectability. In both cases their sense of validation was self-grounded and culturally supported. In many ways their choice of life was a variation on the same theme: the all-too-human attempt to justify ourselves and so to free ourselves from God.

Christians too, can fall into this trap, substituting some kind of self-validation for the validation that comes only from God. They might align with the bourgeoisie and seek their validation in respectability, or perhaps they reject the values of the bourgeois culture and practice a form of life they hope will bring the divine tick of approval. Both approaches will ultimately fail; our only hope of genuine freedom and authenticity is seek our justification in Christ alone.

Yet whatever gain I had, these I have come to regard as loss because of Christ. More than that, I regard everything as loss because of the surpassing value of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord. For his sake I have suffered the loss of all things, and I regard them as rubbish, in order that I may gain Christ and be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but one that comes through faith in Christ, the righteousness from God based on faith.

(Philippians 3:7-9)

[1] Heller, Zoe, “Mick Without Moss” New York Times Magazine, December 3, 2010 http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/05/t-magazine/5well-mick-dek.html?pagewanted=all [Accessed: March 21, 2014]

[2] Alain De Botton, Status Anxiety, ABC DVD 2004. The segment begins at 14:32 in episode 3. Start earlier if you want to watch his interviews at a nudist colony. Don’t say I didn’t warn you!

Too soon? I like the mix of autobiography, culture and theology in your post. But we don’t know why L’Wren killed herself, and it may have had little to do with bohemianism and sexual libertinism. (I know you didn’t join those dots, but I felt you might have been hinting at them.)

Bohemianism is a little passe now. But the Bloomsbury group were more than libertines. Many of them were great thinkers and artists. Today people are transgressive and boring, which the Bloomsburians could never be accused of.

But I suppose my main question back at you is whether the Christian doctrine of justification by faith is actually answering the same question that Bohemianism was trying to answer? There’s a similarity of language (‘validation’) – but wasn’t it more about reacting against the confines of respectability? They threw the baby out with the bathwater, but recognised that respectability wasn’t the point of life, something Jesus would have agreed with.

Thanks Nathan. I was not joining the dots, as you say, and not hinting at a possible cause of death either. L’Wren’s death is a tragedy, regardless of what one thinks of Jagger and his choices, and whether or not there actually was any connection there. I did use the verbal link in Jagger’s statement to connect with the topic that had arisen in our class: that really, was the extent of the connection I was making.

I agree with you that the Bloomsbury group were creative and recognised artists, and far more interesting than those who break rules simply for the sake of self-indulgence. My reaction was more to the granddaughter’s comment concerning self-validation, which could well be her interpretation of what was going on, rather than the participants’ self-understanding of what they were doing. If I may paraphrase Paul – “respectability is nothing; non-respectability is nothing. What matters is the righteousness that comes through faith in Christ, a faith that works with love.”

I appreciate your comment!