This sermon was delivered by Barth on April 21, 1912 to his congregation in Safenwil where he had been pastor for just over a year. The First World War was still two years away and Europe had not yet lost its modern sense of triumphal optimism. The newly minted pastor was just twenty-five years of age when he delivered this sermon.

In this sermon we see Barth the young liberal pastor at work. His text is not Scripture but a world event. Although he does use a biblical text at the head of his sermon, he does not exposit the text or discuss its meaning. Rather he uses it for an idea that he then applies to the subject matter at hand. For this Barth, God speaks to and addresses us through these events, though we must make the meaning from them.

For I believe that, just as we may not approach events such as this one out of curiosity and a thirst for sensation, nor may we disregard them in silence and indifference, however much daily newspaper reports might cause us to do so. Rather, they should speak to us. For through them God addresses us with a power and urgency that we only rarely perceive: concerning the greatness and nothingness of human beings who are so like God, and yet so unlike him, concerning the wrath and mercy of the eternal God, who reigns in and over our destinies, sometimes close at hand and tangibly, but sometimes infinitely far away and mysteriously. God speaks in this way even through a tragedy like the one which has shocked the entire civilised world this week, and we cannot fail to hear, nor may we (cited in Johanson (ed.), The Word in this World: Two Sermons by Karl Barth, 31-32).

Barth assumes that we can read the will and purpose of God in and through the events of the world. The “divine spirit in humanity” is equated with human progress, creativity and inventiveness. God wills this progress, this mastery over nature (36).

We see also the young socialist pastor at work:

Yesterday in the “Freier Aargauer” newspaper the sinking of the Titanic was referred to as a crime of capitalism. After everything that I have now read about it I can only agree. Indeed, this catastrophe is a crude but all-the-more clear example to us of the essential characteristics and effects of capitalism, which consists in a few individuals competing with each other at the expense of everyone else in a mad and foolish race for profits (40).

Barth even notes that the president of the shipping company “is among those who have been rescued—unfortunately, we are almost tempted to say” (40)! The system of capitalism is the real cause of the disaster, the competitive practice based on self-interest at the expense of others. This system must be replaced by a common communal system of labour.

The argument of the sermon develops in three points. First, Barth addresses the hubris of humanity which draws divine judgement from God. Second, he insists that this hubris is grounded in self-interest and leads to destruction. Finally, the way of Christ, or of mercy, is seen in the self-sacrifice of some ordinary sailors that others might live. This spirit must prevail.

So this shipping disaster doesn’t merely point up our helplessness and our faults, our broken arrogance and our secret egoism. Nor does this [mercy] just proclaim to us our transience and its cause. It declares to us with a clarity we rarely experience that God’s purposes are advancing in the world. One senses something of how Christ is becoming an ever greater force in the world, when one reads of those who did not seek to save themselves but did their duty, who ultimately did all they could, not for themselves but for others, who silently and nobly retreated in the face of death to allow those who were weaker than them to continue on the path of life. In view of facts such as these, it takes great unbelief to keep referring to our age as evil and godless (41-42).

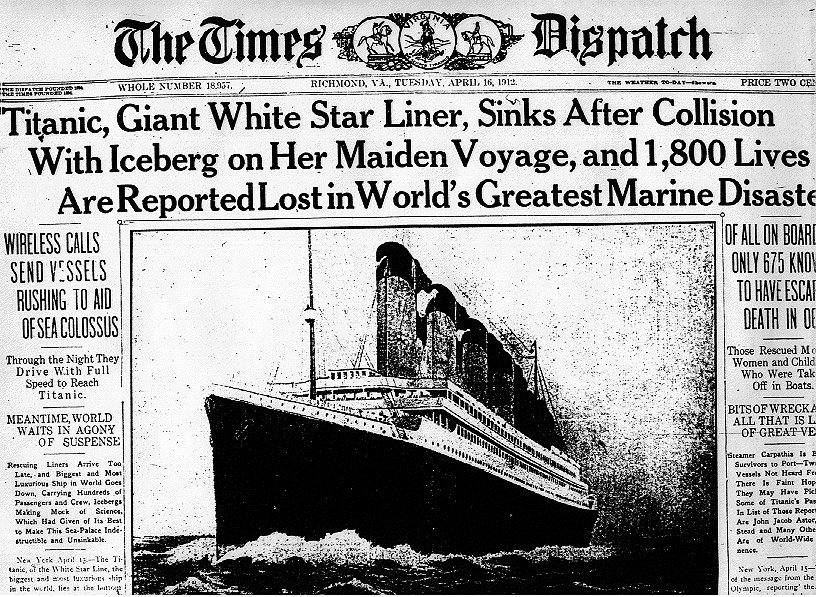

As a communicative exercise, it is possible to appreciate Barth’s style and rhetoric. He draws on a contemporary event that has captivated the daily press and is no doubt prominent in the thought and discussion of his parishioners. He describes in some detail the magnificence of the ship with respect to the feat of its engineering and the luxury of its appointments. The reader can sense the energy and pastoral concern with which the sermon might have been delivered.

As a sermon, however, some commentators have given Barth a great Fail. Barth himself lamented, in later life, about this sermon delivered in his “misspent youth.” Why the concern? A number of reasons might be given, but primarily, Barth later came to expect the biblical text to be the master of the sermon, something obviously not the case in this sermon, focussed as it is on a contemporary event. The sermon is more social comment than biblical exposition. More problematic, Barth does not preach Christ at all in this sermon, but uses the name of Christ—only once in the sermon—as a cypher, or as a symbol for an ideal of human and social progress.

Barth’s liberal optimism came crashing down only two years later with the onset of the war which forced a radical re-evaluation of his theology. The anthropological orientation and natural theology will give way to a more thorough-going theocentric orientation and theology of revelation. More significantly, in his search for a new theological starting point, Barth will discover the “new world in the Bible.”