On the Mystery and Goodness of Humankind

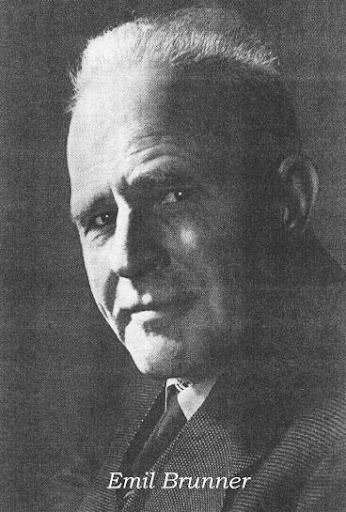

What is man? Neither merely dust, nor merely animal, nor a god. As Brunner turns to the Bible to answer this question he finds that humanity is created being, so that whatever we are, we are because God has made us so. Brunner bats away the scientific question concerning the mechanism God used to create humanity: “it is not a critical question for faith” (38). Clearly God uses means as the instruments of his work—such as dust, or human parents—but the work done remains God’s work.

What is man? Neither merely dust, nor merely animal, nor a god. As Brunner turns to the Bible to answer this question he finds that humanity is created being, so that whatever we are, we are because God has made us so. Brunner bats away the scientific question concerning the mechanism God used to create humanity: “it is not a critical question for faith” (38). Clearly God uses means as the instruments of his work—such as dust, or human parents—but the work done remains God’s work.

Humanity is created in God’s image which distinguishes the human from all other creatures and establishes a similarity of the human creature to God. “What distinguishes man from the rest of creation is the share he has in God’s thought, that is, reason as distinguished from perception, which the animal also possesses” (39). More fundamentally, humanity is not merely created,

by the Word of God but for and in his Word. That means, God created man in such a way that he can receive God’s Word. That is reason in its true sense. Man really becomes man when he perceives something of God. … Man has been so created by God that he can become man only by perceiving God, by receiving God’s Word and—like a soldier repeating a command—repeating God’s Word. … When he says that in his heart homo sapiens becomes humanus. … We are man to the extent that we let God’s Word echo in our hearts. We are not simply men as a fox is a fox. But we are men only when God’s Word finds an echo in us. To the degree that this fails to happen we are inhuman (39, original emphasis).

Two features of this exposition bear reflection. First, ‘reason,’ for Brunner, is true to the extent that it responds and corresponds to the Word of God. The instrumental use of reason which has so distinguished the human from the rest of creation must be supplemented or perhaps crowned with this additional use if humanity is to be truly human, to fulfil its destiny as the divine image.

This infers that, second, Brunner views human existence as a project of becoming. We are human but must become, as it were, what we truly are. What we truly are is what God has intended and created us to be rather than what we find ourselves as. Homo sapiens must ‘become’ humanus. The Latin term can simply mean ‘human’ but also carries the nuances of humane or cultured or refined. This ‘becoming’ is a matter of positive response to the Word of God addressed to us. The person must perceive God, receive God’s Word, and let it echo in their heart. “The freedom to say yes or no to God is the mystery of man” (40). We have this freedom only because we are addressed by God. In this way we become his image, corresponding to him in his Word.

Failure to answer God’s Word addressed to us leaves us ‘inhuman.’ I don’t think Brunner intends this pejoratively, though it is tempting, perhaps, to see here a reference to the developing political and social situation of Germany in the mid-1930s. Rather, we fail to realise our existence as ‘the image of God.’ We are still ‘human’ in terms of our species but now without God as it were, less than what God intends for his creation. We are still endowed with the remarkable capacities God has given us but they now function in ‘inhuman’ ways, warped perhaps by our selfishness. For Brunner as for Calvin, we can only truly see and know ourselves as we perceive God; we know ourselves in his light.

To know ourselves truly, however, is also to understand that we are sinners. From a human perspective there is no one who is wholly good or wholly bad for we are all a mixture of both, though some people tend more the one way and some the other. In a biblical perspective, however, ‘there is none that does good, no, not one…’ To be a sinner is to be “bad at heart, infected with evil at the core” (41).

Sin is a depravity which has laid hold on us all. It is a radical perversion from God, disloyalty to the Creator who has given us so much and remains so loyal, an insulting alienation from Him, in which all of us, without exception, have shared (42-43).

Brunner uses the image of two people on a train, one sensible and the other stupid. But the point is that they are both on the same train and both heading in the same direction—in this case, away from God. This perversity, this evil that has captured the human heart, is inexplicable. We cannot explain sin nor even perceive it until it is shown to us in the death of Christ:

It is not until we see how much it cost to remove the stone between us and Him, that we understand how great was the weight of sin’s guilt. Christ shows us how completely the whole movement of life is in the wrong direction (44).

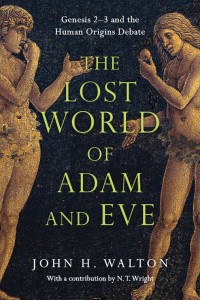

Human Origins: How did we come to be here?

Human Origins: How did we come to be here? good’ be understood in terms of some kind of metaphysical perfection, or might it be understood in terms of the value God the Creator places upon his work? English theologian Colin Gunton suggested that, “Rather like a work of art, creation is a project, something God wills for its own sake and not because he has need of it” (Colin E. Gunton, “The Doctrine of Creation,” in The Cambridge Companion to Christian Doctrine, 142). Such an interpretation suggests that God’s work of creation was not the end of his purpose, but the beginning of a project playing out across history and moving toward a divine purpose and climax. In this view, the immanent God accompanies his creation, at times doing new things, providentially guiding the creation toward his appointed goals.

good’ be understood in terms of some kind of metaphysical perfection, or might it be understood in terms of the value God the Creator places upon his work? English theologian Colin Gunton suggested that, “Rather like a work of art, creation is a project, something God wills for its own sake and not because he has need of it” (Colin E. Gunton, “The Doctrine of Creation,” in The Cambridge Companion to Christian Doctrine, 142). Such an interpretation suggests that God’s work of creation was not the end of his purpose, but the beginning of a project playing out across history and moving toward a divine purpose and climax. In this view, the immanent God accompanies his creation, at times doing new things, providentially guiding the creation toward his appointed goals.