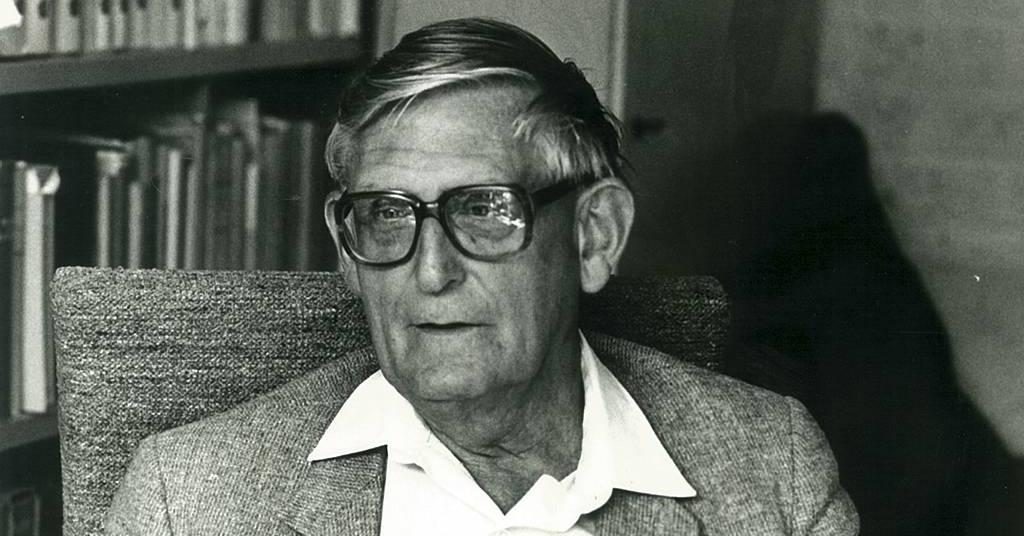

Although I cannot agree with some aspects of Berkhof’s christology, I have long appreciated his brief chapter on Jesus’ Life and Humanity (Christian Faith, 293-299).

Although I cannot agree with some aspects of Berkhof’s christology, I have long appreciated his brief chapter on Jesus’ Life and Humanity (Christian Faith, 293-299).

In the history of theology the life of Jesus has always stood in the dark shadow, on the one hand of the two-nature doctrine, on the other of the doctrine of reconciliation. … Even today in all kinds of orthodox instruction in the faith the impression is given that Jesus came to earth only to suffer and to die. The fact that the Apostles’ Creed has no article about Jesus’ life, but immediately moves from “born” to “suffered” is also responsible for that.

Berkhof is correct to insist on the theological significance of Jesus’ life, and not simply his “humanity” understood in a vague or abstract way. Perhaps in the history of theology, it is the Anabaptists who have best understood this. That Jesus was born, grew up as a child, as part of a family, that he worked, hungered and thirsted, loved and served, taught and healed, had compassion, had friendships, suffered and prayed, fasted and went to synagogue, and so on, cannot be incidental to theology, to an understanding of his person and work, or our own person and work.

For Berkhof, Jesus is representative humanity, himself truly human and exhibiting a truly human life. This life was exemplified in his love for and obedience to the Father, and his passionate willing of the Father’s will. As representative humanity, Christ accomplished a kind of priestly work, establishing the covenantal order between God and humanity in his own person, and bringing forgiveness and healing to guilty and wretched humanity.

As such the truly human life is one bound to God in love, fellowship and obedience, and as such, truly free. Jesus enjoyed, on the basis of his fellowship with the Father, an utter freedom,

with respect to the temple and the cult, synagogue and commandment, priests and scribes, sabbath and government, mother and brothers, food and clothing, property and money, popularity and the power of the state. … It was the fruit of a strong carefreeness, which in turn was born from the absolute priority of the Father and his gracious lordship” (296-297, original emphasis).

Again,

here is the complete structure of what it is to be man, in his threefold relationship to God, the neighbor, and nature. Here is also the highest quality of what it is to be man, as love and freedom. Here human existence has reached its full maturity and therefore has fully become God’s partner and instrument.

Berkhof notes that this account of Jesus’ humanity is typically summed up in the term “sinlessness.” Berkhof considers this an “unfortunate” term as it is “too negative, too static, too limited” (297). He does, however, insist that Christian faith

stands or falls with the belief in Jesus’ sinlessness. But like us all, he had to become what he was. … Jesus did not know that in advance and he felt the full impact of the opposing forces. He had no idea of his sinlessness on which he, encouraged by it, could fall back. … Instead of the negative “sinlessness,” we have in the heading used the word humanity to express the core of Jesus’ life (297).

Berkhof opts for a functional kind of sinlessness in which Jesus did not sin, rather than Jesus was “without sin” (he compares the AV with the RSV to illustrate this difference). It may be that with respect to his being, Jesus was constitutionally unable to sin (this is my language, not Berkhof’s), but “human existence realizes and discloses itself only in a series of choices whose outcome is also for the chooser uncertain in advance, but which in retrospect yields a coherent life pattern” (299).

To consider the question otherwise, suggests Berkhof, is to render Jesus less than human with respect to our perspective of him. This is a pastoral issue, but perhaps also an accurate representation of the New Testament witness with respect to Jesus’ sinlessness.