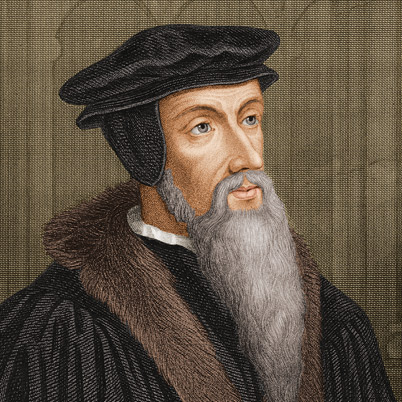

I came across this note as I read a little of Calvin this evening. I was in the Institutes I:14:iv on the doctrine of creation where Calvin is beginning his discussion of the angels. He writes to head off the kind of teaching that indulges in endless curiosity and speculation not tethered to Scripture. His words are still apt today:

I came across this note as I read a little of Calvin this evening. I was in the Institutes I:14:iv on the doctrine of creation where Calvin is beginning his discussion of the angels. He writes to head off the kind of teaching that indulges in endless curiosity and speculation not tethered to Scripture. His words are still apt today:

Let us remember here, as in all religious doctrine, that we ought to hold to one rule of modesty and sobriety: not to speak, or guess, or even to seek to know, concerning obscure matters anything except what has been imparted to us by God’s Word. Furthermore, in the reading of Scripture we ought ceaselessly to endeavor to seek out and meditate upon those things which make for edification. Let us not indulge in curiosity or in the investigation of unprofitable things. And because the Lord willed to instruct us, not in fruitless questions, but in sound godliness, in the fear of his name, in true trust, and in the duties of holiness, let us be satisfied with this knowledge . . .

The theologian’s task is not to divert the ears with chatter, but to strengthen consciences by teaching things true, sure, and profitable.

(See: Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, Library of Christian Classics. Editor: John T. McNeill; Trans. Ford L. Battles, volume 1:164.)

Calvin reminds us of the limits our knowledge and so counsels epistemological humility. It is evident that he views Scripture as an inspired and authoritative source of theological knowledge, and that what is given us in Scripture might be profitably taught, learned, and believed. But not everything we might want to know is given us in Scripture. Standing behind this admonition is Deuteronomy 29:29: “The secret things belong to the Lord our God, but the things revealed belong to us and to our children forever, that we may follow all the words of this law.”

Of course, not all questions are fruitless. Many questions are necessary if we are to understand Scripture in both its parts and as a whole. Many more are necessary if we are to understand its significance and relevance to our everyday lives. Calvin certainly understands this as his own work testifies. But he is against the kind of mystical or merely academic approaches to Scripture and theology that neglect what he considers basic: the pastoral purposes for which Scripture is given – something also found in Deuteronomy 29:29.

The pastoral orientation of Calvin’s theological work is clear. In this, he differs not at all from Luther–see my discussion of Luther’s pastoral theology. In the citation given above, Calvin provides a framework for discerning that which is pastorally useful: that which edifies and strengthens the conscience; that which nurtures godliness and the fear of the Lord, true trust, and holiness. We might want to add to the kinds of pastoral outcomes we seek to nurture in the lives of God’s people: engagement in community and mission, the pursuit of just relationships, concern for the poor, etc. Nevertheless, Calvin’s concern for trust, holiness and a good conscience before God is also warranted.

I found this a salutary reminder that theological enquiry is never an end in itself but a means of being drawn more deeply into a life of faithfulness before God, and a participation in his creational and redemptive purposes – as revealed in Scripture.