In twelfth century Western Europe, independent schools were springing up alongside the older cathedral schools as a precursor to the development of the universities. There was a market for students as more and more people wanted the kind of education that prepared them for the growing civil service required by both church and state. According to Gillian Evans,

In twelfth century Western Europe, independent schools were springing up alongside the older cathedral schools as a precursor to the development of the universities. There was a market for students as more and more people wanted the kind of education that prepared them for the growing civil service required by both church and state. According to Gillian Evans,

A school did not need buildings or organization or a syllabus. Would-be masters could simply set themselves up and lecture to students, so they needed to be in places where potential fee-paying students might be found. There was rivalry. Masters tried to capture one another’s students, sometimes adding critical comments about one another’s opinions in their lectures….

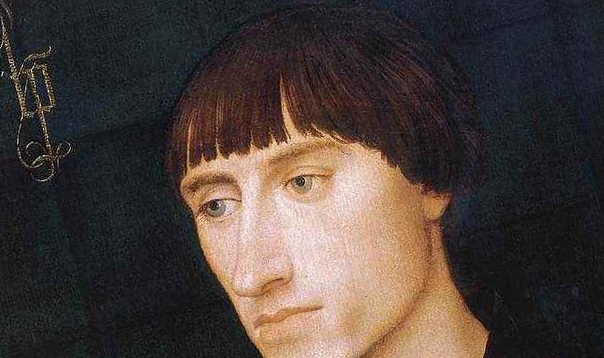

One of the most notorious of these wandering masters, Peter Abelard (1079-1142) describes in his History of My Calamities how he went to hear Anselm of Laon (d. 1117) lecture at the cathedral school at Laon, with the express purpose of capturing some of his students. Abelard had already made his name as a daring logician and now he wanted to move on to theology, an obvious career move because it was regarded as a more advanced and prestigious subject. … Abelard was not a trained theologian. He had, however, skills in linguistic analysis from his knowledge of logic, and he began to apply these to the interpretation of the text of Scripture with disturbing results. Students loved this for its danger and novelty. They flocked to hear him. He was able to set up a school in Paris at St Geneviève on the left bank of the Seine (Evans, The Roots of the Reformation, 161-162).

I had to smile at Abelard wanting to “move onto theology, an obvious career move…”, and also at the rivalry between teachers and schools. Some things change and some things don’t.

It is also evident that some things about students haven’t changed much either, though perhaps this can be forgiven. Part of the joy of education is the opportunity to explore novel and even dangerous ideas. Problems occur when such education is broken off too quickly, and the novel is embraced uncritically, or worse, because it is novel. Sometimes, though, the novel may prove to be a breakthrough, a new paradigm that advances knowledge and opens new vistas of understanding. This has happened time and again in the history of theology. It is evident, however, that Evans does not think much of Abelard’s innovations.

Re your final paragraph: Yes, Mike, there’s a lot of work in developing a perspective that appears novel, since we need to understand what others have said before we can challenge the prevailing Western mindset. Then there’s the process of wrestling with how to express it so it gets a hearing, and then submitting it to peer review where it can be misunderstood, ignored, dismantled, or proved erroneous.

Theology isn’t too hard, but it is demanding work.

Hi Allen, your comment reminds me that there are at least two ways of being novel. There is the more formal and academic route, in which someone tests an idea, develops it, gathers evidence and addresses objections, etc (think Liberation Theology, Open Theism, etc). The other route, and possibly the one Gillian Evans had in mind, is a more populist approach, where someone has “a revelation”, or seeks notoriety, acclaim, a following, money, etc (think Evans’ view of Abelard, the prosperity gospel, etc). The first avenue is indeed hard work and may attract all kinds of opprobrium, even if the novel eventually becomes mainstream (think Thomas Aquinas’ assimilation of Aristotelianism into Western theology); the second avenue may never even register a blip on Christian consciousness, or it may become a popular and enduring heterodox movement or doctrine within the church (think Mariolatry, the doctrine of limited atonement).