Nearly all the wisdom we possess,

Nearly all the wisdom we possess,

that is to say, true and sound wisdom,

consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves.

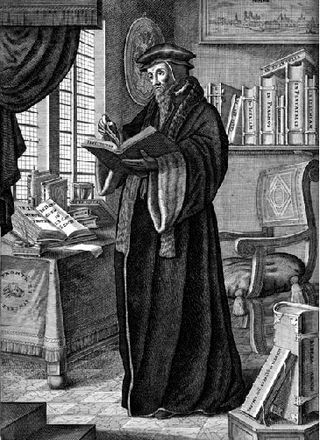

So begins Calvin’s monumental Institutes of the Christian Religion. In tonight’s class we have our first seminar based on the opening chapters of Book 1. By the end of the semester we will have worked our way through Book 1 and into the first chapter or two of Book 2 (except for the chapter on the Trinity: we will keep that for next semester so the students have something to look forward to!).

I wonder how this cohort of students will respond to the great Swiss Reformer? In the past, I have had some students appreciate him, some despise him, some find him difficult to read and comprehend, and some argue that they should not have even to read him.

I have encouraged to class to engage him rigorously, carefully and with due respect. I consider the Institutes to be the most important Protestant theology yet penned, because it gathered and systematised the thought of the early Reformation in its most complete and exalted form, and set a pattern for theological reflection and exposition that continues until this day. That does not mean, of course, that we must adhere to all of his positions. We are free to question his proposals, dispute with him, even reject him if we believe we have sufficient grounds. The problem too often, however, is that we think we can dismiss Calvin before we have read him, listened to him, heard him, understood him. In such cases our rejection says much more about us than it does about him and his work.

Back to Calvin’s opening words: what does he mean? I think I am still learning the depths of this seemingly simple statement. For Calvin, we live and move and have our being in God (cf. Acts 17:28). Every moment of our existence is lived in the immediate presence and under the immediate rule of this divine sovereign. If this is the case, then “true and sound wisdom” is learning to acknowledge and accept this as the reality of our existence and to live in its light. That is, we are learning to be God’s creatures, and so to acknowledge God as Creator, Ruler, Sustainer and God. We are learning to take our place under his reign, and so find ourselves lifted up and freed.

This knowledge becomes the “law of our creation.” In knowing God we come to know ourselves, our place in the cosmos, the fundamental principle of our life, the goal and telos of our existence. So thus, we might begin to gain wisdom. The great tragedy, of course, is that this is precisely what we refuse to do.

Besides, if all men are born and live to the end that they may know God, and yet if knowledge of God is unstable and fleeting unless it progresses to this degree, it is clear that all those who do not direct every thought and action of their lives to this goal degenerate from the law of their creation (I.iii.3).

Finally, it is also worth noting that Calvin’s goal is wisdom – sapientia – rather than abstract knowledge. He is not interested in a philosophical or speculative knowledge that seeks to understand all mysteries but does not issue in a life of love and reverence towards God.

I am truly disappointed to have missed this unit, Michael…..

And I would have loved to have you in class as well Ian! But there is only so much one can do…